Pollination ecology is often fair-weather work. As most insects are ectothermic, the majority of pollinators tend to be active only during warm and sunny spells. During cold, windy or rainy weather most pollinators are hiding out, keeping safe and warm in sheltered areas. However, in the world of entomology there are always exceptions to the rule. This is most certainly the case with pollinators of lowbush blueberries

Pollination ecology is often fair-weather work. As most insects are ectothermic, the majority of pollinators tend to be active only during warm and sunny spells. During cold, windy or rainy weather most pollinators are hiding out, keeping safe and warm in sheltered areas. However, in the world of entomology there are always exceptions to the rule. This is most certainly the case with pollinators of lowbush blueberries

The lowbush blueberry is a native plant widely found throughout eastern North America. The plant thrives in open areas, and is associated with well-drained acidic soils. They spread asexually through rhizomes, and a single plant may cover dozens of square meters. Each of these plants is referred to as a clone. Lowbush blueberry fields are formed by felling trees, and by cutting back or removing competing plants. After decades of hard work and patience, one is left with an area primarily composed of lowbush blueberry.

A lowbush blueberry field in Mt. Thom, Nova Scotia. You can spot the various clones, which range in amount of stem-pubescence, flower colour, height, and leaf colour. [P.Manning]

Like many other plants, blueberries are not self-compatible. This means a flower of one clone, will require deposition of pollen from a different clone to achieve successful pollination. If a flower is not sufficiently pollinated, no fruit will form.

But there’s a catch, the flowers of the lowbush blueberry are downward facing bell-shaped flowers. Pollen is not likely to be wind-blown onto a receptive stigma because it is hidden safely within the corolla (protective petal sheath) of the flower. Instead pollination relies on an insect visitor to deliver the pollen.

Lowbush blueberry plants invite insects to complete this service for them by offering food rewards: nectar and pollen. While pollinating insects go in for sustenance – the tiny pollen grains are transferred from the stamen, and adhere to the visiting insect. With a little luck, these pollen grains will be transmitted to a receptive stigma: pollinating the second flower.

As fields are relatively homogenous with blueberry flowers, native pollinators alone may not always be able to achieve maximum fruit-set. To give the fields a boost, farmers introduce European honey-bees to the mix, where yield has been shown to increase linearly up to stocking densities of 4 hives/hectare. But honey bees are picky. They don’t tend to fly when: the skies are too overcast, wind is too high, the temperature dips down too low, or when it’s foggy. If you’re familiar with weather patterns in eastern North America, you’ll know that May/June (when lowbush blueberries bloom) is likely to experience every sort of inclement condition possible; meaning honey bees efforts alone just won’t cut it 100% of the time.

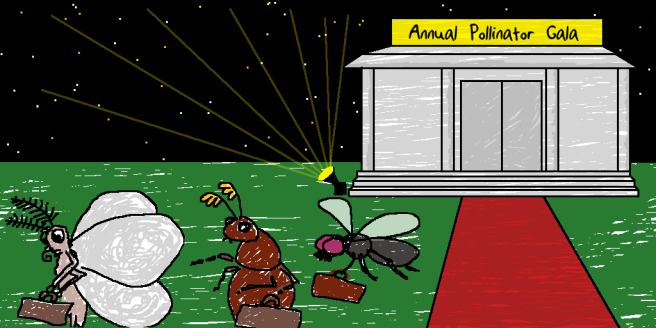

It’s here where we rely on our other pollinators. Native bees (both of the solitary and bumble variety), various flies, moths, beetles, and butterflies are all abundant in lowbush blueberry fields during the day. However, we know very little about insect pollinators that are active at night.

In 2011, a team from Dalhousie University set out to quantify just how much pollination was being performed by these diverse, nocturnally active communities. The team marked stems in netted exclosures, and monitored the flower-to-fruit progression of four experimental treatments: Accessible only during daylight hours, Accessible only during night-time hours, Accessible 24-hours, and Insects excluded 24-hours. The team also set overnight malaise traps to learn which insects were flying during the cover of night. Their results were very surprising.

In an article published in the Canadian Journal of Plant Science, the team found that significant fruit-set occurred during night-time hours. This fruit-set achieved by nocturnal pollinators was equivalent to approximately two-thirds of fruit-set achieved in the accessible 24-hours pollination enclosures. When comparing the number of ripe berries at harvest, nocturnal pollinators contributed pollination services yielding to approximately one-third of the number of ripe berries in the 24-hours open treatment. This suggested that nocturnal insects played an important role in pollination services. The malaise trap yielded many moths ( primarily Geometridae, Gelechiidae, and Tortricidae) and flies (Chironomidae, Cecidomyiidae, Ceratopogonidae, Culicidae) – but could not confirm whether these taxa were pollinating insects.

In the summer of 2012, we began another experiment to learn a little more about nocturnal pollination of lowbush blueberry. Using light traps, and sweep netting we sampled insects from the field during night-time hours. Then back at the lab, we identified our captures, and using a neat little method – removed pollen from the insects with a tiny piece of fuschine-stained agar. By comparing any pollen we found to a reference sample, we could determine whether the insects had come into contact with blueberry pollen (still not conclusively determining whether they were pollinating the plants, but none-the-less a step in the right direction).

Our results were quite surprising, and very exciting. By selecting insect families where >30 individuals were collected, we found that a high proportion of individuals from many families were carrying lowbush blueberry pollen : Curculionidae (32%), Geometridae (22%), Noctuidae (19%), Tachinidae (14%), Scarabaeidae (12%). This simple experiment gave us an interesting snap-shot into just how diverse lowbush blueberry pollinator communities could be. The weevils finishing at the front of the pack was particularly surpising, and I’m particularly curious to find out whether they are effective pollinators or just grabbing a free snack. If anyone wants to run this experiment, I’d love to chat – please drop me a line!

These experiments demonstrate just how important it is to consider just how diverse insect pollinators are. While bees are undoubtedly of paramount importance, there’s a lot more to the story. How can agriculturally systems be optimally managed, if we don’t even know the entirety of species acting as pollinators?

Nocturnal pollinators could play am important complementary roles to pollination by bees. Many moths can generate body-heat by shivering, and can fly in far colder conditions than what is possible for bees. Beetles walk between plants, which is far less energetically expensive than flying – and is possible in all sorts of weather. Tachinid flies are parasitoids whose larvae consume caterpillars of pest moths like the blueberry spanworm, while potentially also wearing a second hat as a pollinator.

So next time you’re chowing down on a handful of blueberries, consider giving a moment to thank a pollinator for the delicious treat. It’s possible that one in every three ripe berries could be attributable to a pollinating insect working the night shift.

References:

Cutler, G.C., Reeh, K.W., Sproule, J.M., Ramanaidu, K., 2012. Berry unexpected: Nocturnal pollination of lowbush blueberry. Can. J. Plant Sci. 92, 707–711.

Manning, P., Cutler, G.C., 2013. Potential nocturnal insect pollinators of lowbush blueberry 3, 1–3.

Thanks Paul. Great article. I used to worry about you out in the dark In the middle of the blueberry patch… When you would be so tired.

>

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Honey Bee Suite and commented:

Nocturnal pollination is something I seldom think about. But this fascinating article by Paul at Poky Ecology describes a host of nighttime pollinators in lowbush blueberry. Really, I had no idea how busy a berry bush in the dark could be.

In conclusion, Paul asks, “How can agricultural systems be optimally managed, if we don’t even know the entirety of species acting as pollinators? Good question. The article also details some of the limitations of honey bees as pollinators, one of my favorite subjects.

LikeLike

How interesting! Never thought about nocturnal pollinators for blueberry. Makes me super curious about how they smell and whether there are different floral scents in the day vs night. Too bad I’ll be coming to Nova Scotia in July this summer when they’re done flowering.

LikeLike

Hi Amy! Thanks for your comment! I think it’s fascinating system – definitely would be something interesting to investigate. Sorry you’ll be missing bloom this year, it’s one of the most wonderful times of the year! However, you could well be back in time for the eating (which is sort of the best part anyway). Safe travels home! -P

LikeLike